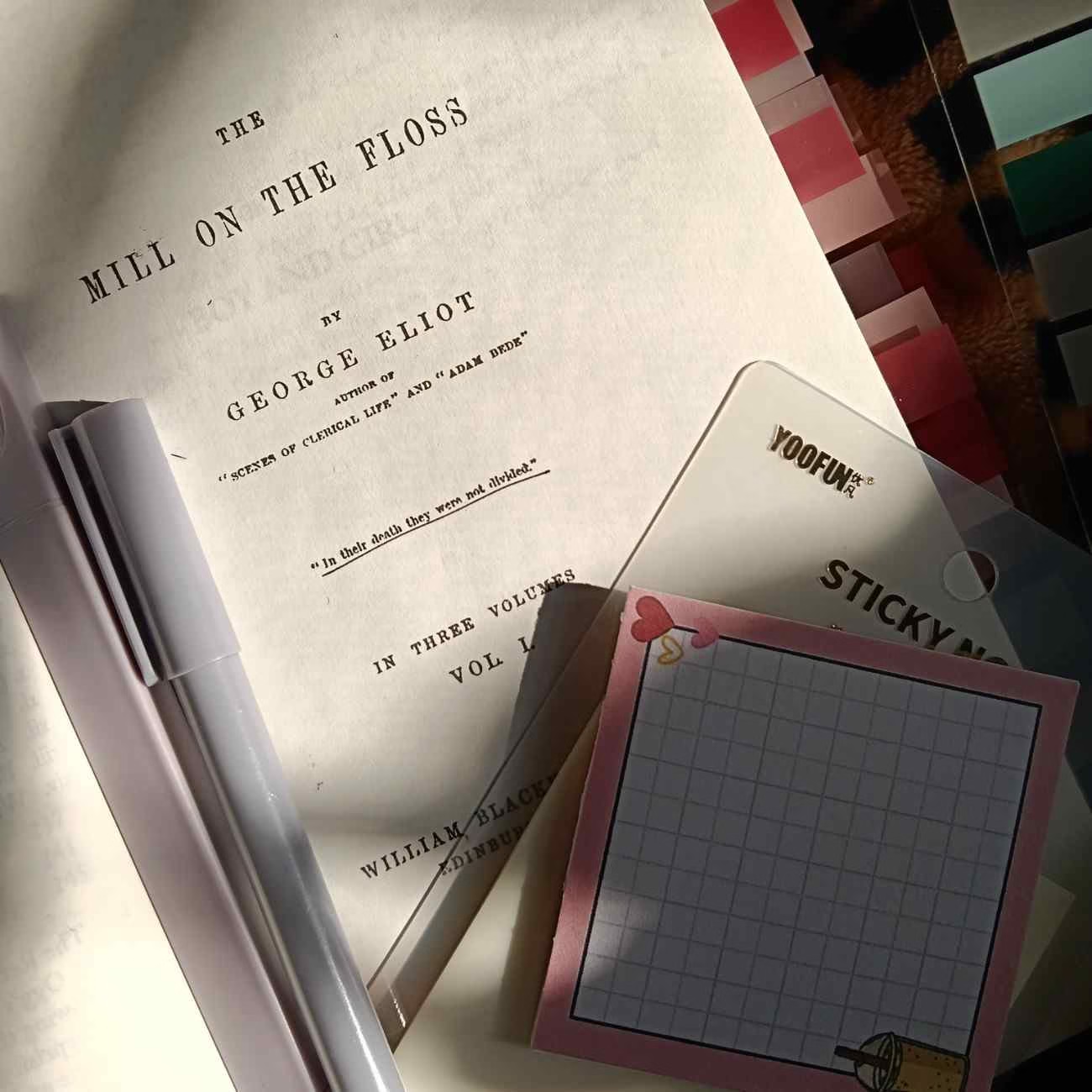

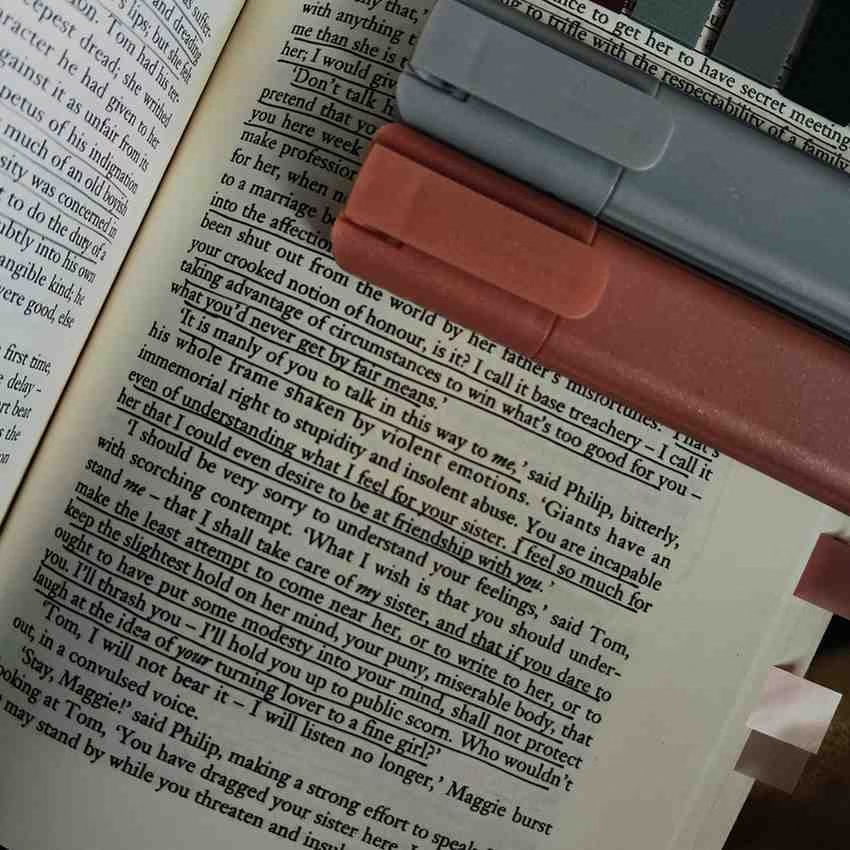

All George Eliot Quotes from “The Mill on the Floss”

I had first read The Mill on the Floss as a part of the three Victorian novels in my semester curriculum.

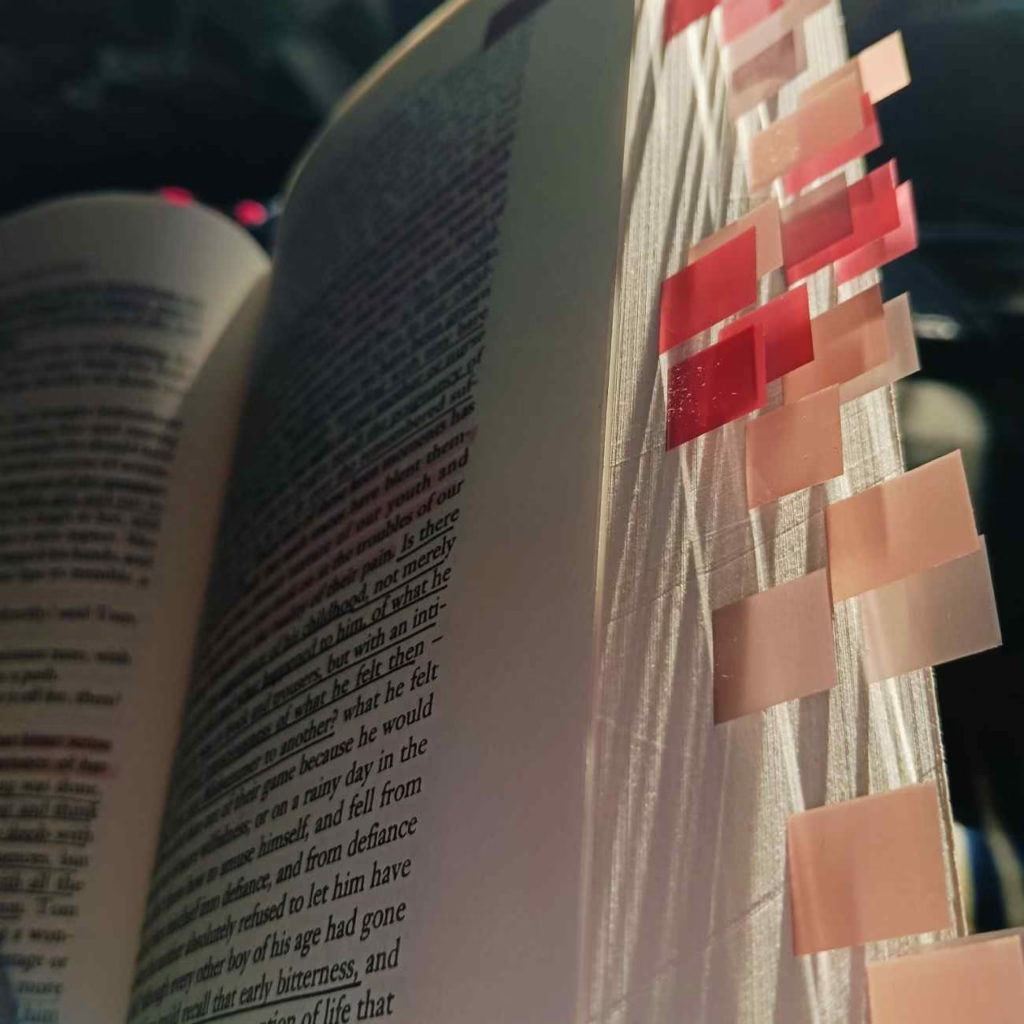

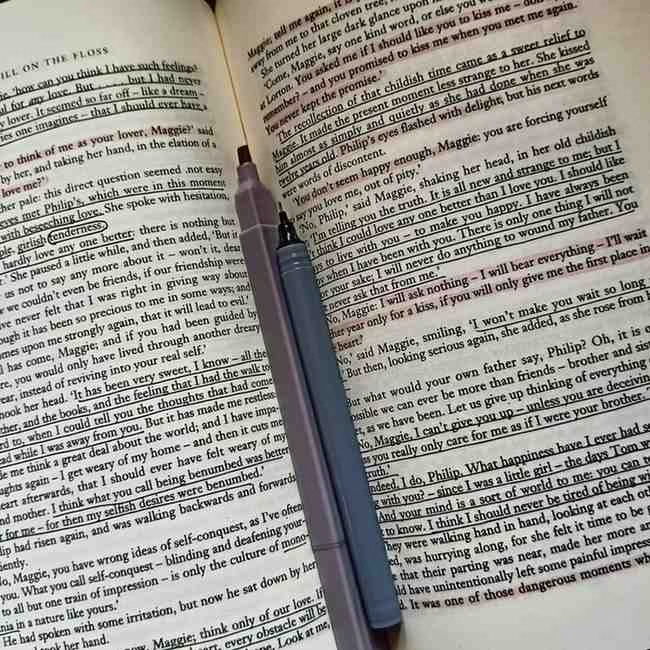

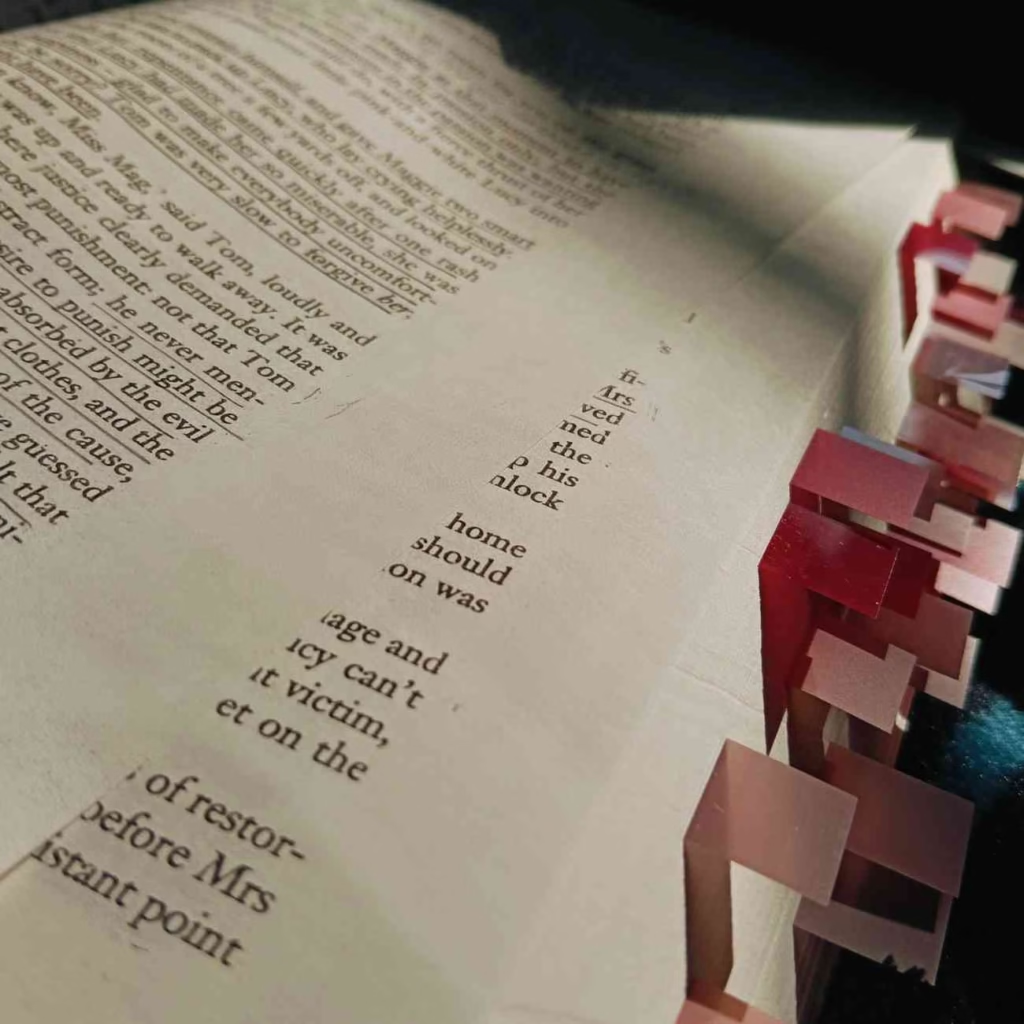

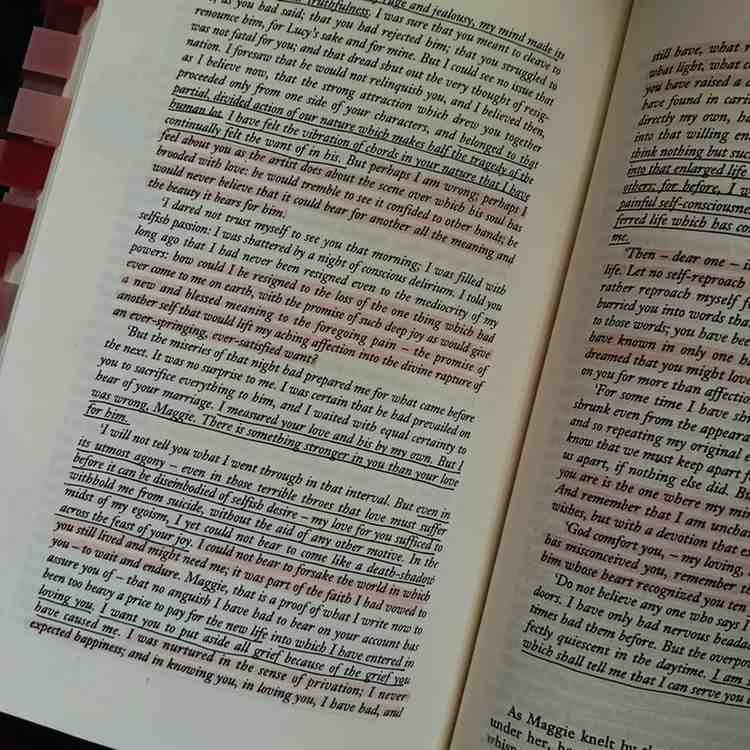

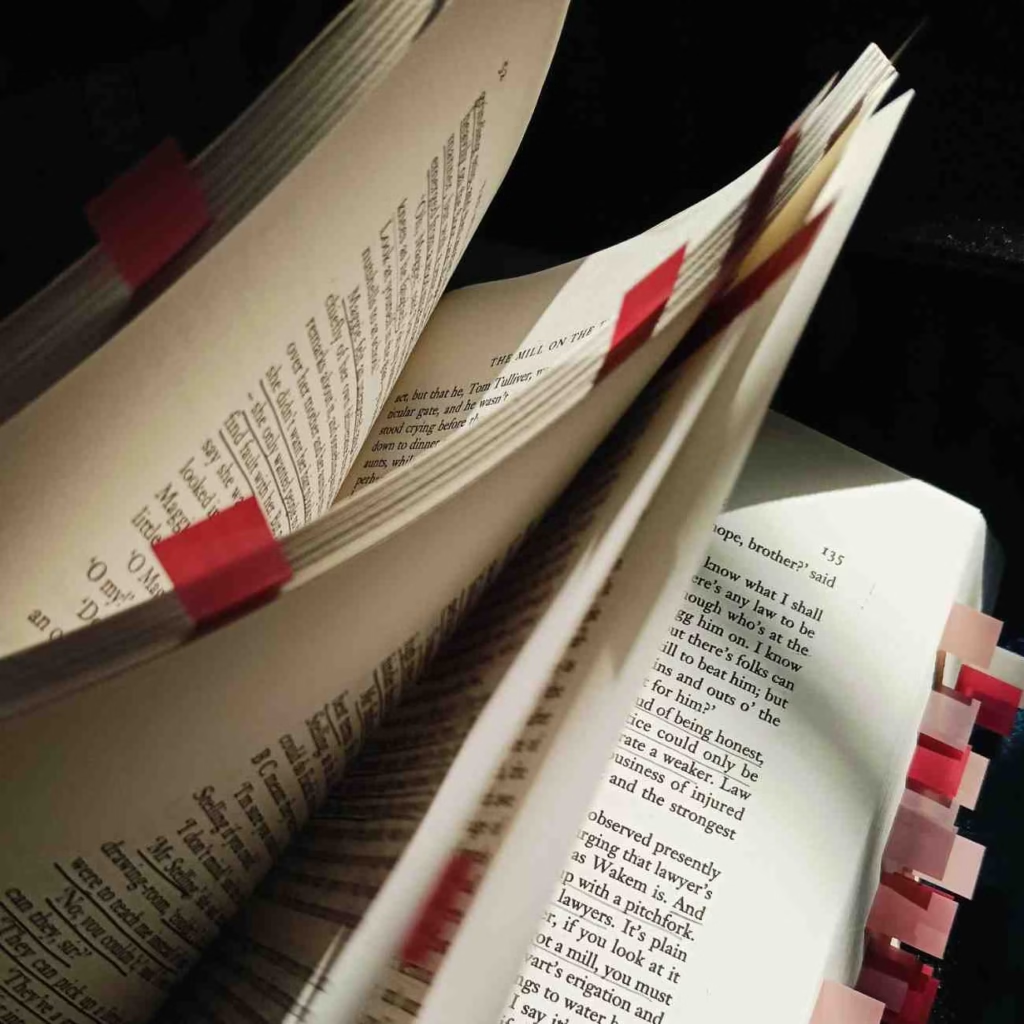

To compile this post, I skimmed the book again and noted down the quotes and lines I had highlighted to form this quote-bank for someone who hasn’t had the time to read the complete book but who wants a reliable source for all the poetic matter of it.

To say that this post took time is not to imply that I did not absolutely enjoy and adore the process, but it is to say that this has thus become a very reliable and a completely extensive list of every quote worth quoting from George Eliot’s beautiful The Mill on the Floss, all in the order in which they appear.

You could share these quotes on your social, or use these quotes in your mini-essays, or just get the feel of having read the book and all its beautiful noteworthy stuff. There are different categories of quotes from The Mill on the Floss, differentiated into lists on the basis on love, childhood, sorrow.

Let’s begin!

Table of Contents

George Eliot Quotes from The Mill on the Floss

Quotes about Childhood

- Life did change for Tom and Maggie; and yet they were not wrong in believing that the thoughts and loves of these first years would always make part of their lives. We could never have loved the earth so well if we had had no childhood in it — if it were not the earth where the same flowers come up again every spring that we used to gather with our tiny fingers as we sat lisping to ourselves on the grass; the same hips and haws on the autumn’s hedgerows; the same redbreasts that we used to call “God’s birds,” because they did no harm to the precious crops. What novelty is worth that sweet monotony where everything is known, and loved because it is known?

- Maggie always looked at Lucy with delight.She was fond of fancying a world where the people never got any larger than children of their own age, and she made the queen of it just like Lucy, with a little crown on her head, and a little sceptre in her hand — only the queen was Maggie herself in Lucy’s form.

- What could she do but sob? She sat as helpless and despairing among her black locks as Ajax among the slaughtered sheep. Very trivial, perhaps, this anguish seems to weather-worn mortals who have to think of Christmas bills, dead loves, and broken friendships; but it was not less bitter to Maggie — perhaps it was even more bitter — than what we are fond of calling antithetically the real troubles of mature life. “Ah, my child, you will have real troubles to fret about by and by,” is the consolation we have almost all of us had administered to us in our childhood, and have repeated to other children since we have been grown up. We have all of us sobbed so piteously, standing with tiny bare legs above our little socks, when we lost sight of our mother or nurse in some strange place; but we can no longer recall the poignancy of that moment and weep over it, as we do over the remembered sufferings of five or ten years ago. Every one of those keen moments has left its trace, and lives in us still, but such traces have blent themselves irrecoverably with the firmer texture of our youth and manhood; and so it comes that we can look on at the troubles of our children with a smiling disbelief in the reality of their pain. Is there any one who can recover the experience of his childhood, not merely with a memory of what he did and what happened to him, of what he liked and disliked when he was in frock and trousers, but with an intimate penetration, a revived consciousness of what he felt then, when it was so long from one Midsummer to another; what he felt when his school fellows shut him out of their game because he would pitch the ball wrong out of mere wilfulness; or on a rainy day in the holidays, when he didn’t know how to amuse himself, and fell from idleness into mischief, from mischief into defiance, and from defiance into sulkiness; or when his mother absolutely refused to let him have a tailed coat that “half,” although every other boy of his age had gone into tails already? Surely if we could recall that early bitterness, and the dim guesses, the strangely perspectiveless conception of life, that gave the bitterness its intensity, we should not pooh-pooh the griefs of our children.

- The children were used to hear themselves talked of as freely as if they were birds, and could understand nothing, however they might stretch their necks and listen.

- While the possible troubles of Maggie’s future were occupying her father’s mind, she herself was tasting only the bitterness of the present. Childhood has no forebodings; but then, it is soothed by no memories of outlived sorrow.

- “Oh, father,” sobbed Maggie, “I ran away because I was so unhappy; Tom was so angry with me. I couldn’t bear it.”/ “Pooh, pooh,” said Mr. Tulliver, soothingly, “you mustn’t think o’ running away from father. What ‘ud father do without his little wench?”

- There is no sense of ease like the ease we felt in those scenes where we were born, where objects became dear to us before we had known the labor of choice, and where the outer world seemed only an extension of our own personality; we accepted and loved it as we accepted our own sense of existence and our own limbs.

- The promise was void, like so many other sweet, illusory promises of our childhood; void as promises made in Eden before the seasons were divided, and when the starry blossoms grew side by side with the ripening peach — impossible to be fulfilled when the golden gates had been passed.

- Tom had so often thought how joyful he should be the day he left school “for good!” And now his school years seemed like a holiday that had come to an end.

- They had gone forth together into their life of sorrow, and they would never more see the sunshine undimmed by remembered cares. They had entered the thorny wilderness, and the golden gates of their childhood had forever closed behind them.

- She went to him and put her arm round his neck as he sat by the bed, and the two children forgot everything else in the sense that they had one father and one sorrow.

- They were very bitter tears; everybody in the world seemed so hard and unkind to Maggie; there was no indulgence, no fondness, such as she imagined when she fashioned the world afresh in her own thoughts.

- “I wish we could have been friends — I mean, if it would have been good and right for us. But that is the trial I have to bear in everything; I may not keep anything I used to love when I was little. The old books went; and Tom is different, and my father. It is like death. I must part with everything I cared for when I was a child. And I must part with you; we must never take any notice of each other again.”

Quotes about Girlhood and Boyhood

- “A woman’s no business wi’ being so clever; it’ll turn to trouble, I doubt.”

- “He was one of those lads that grow everywhere in England, and, at twelve or thirteen years of age, look as much alike as goslings.”

- “I’ve got a great deal more money than you, because I’m a boy. I always have half-sovereigns and sovereigns for my Christmas boxes, because I shall be a man, and you only have five-shilling pieces because you’re only a girl.”

- Tom was only thirteen, and had no decided views in grammar and arithmetic, regarding them for the most part as open questions, but he was particularly clear and positive on one point — namely, that he would punish everybody who deserved it. Why, he wouldn’t have minded being punished himself if he deserved it; but, then, he never did deserve it.

- Tom, indeed, was of opinion that Maggie was a silly little thing; all girls were silly — they couldn’t throw a stone so as to hit anything, couldn’t do anything with a pocket-knife, and were frightened at frogs.

- She didn’t want her hair to look pretty — that was out of the question — she only wanted people to think her a clever little girl, and not to find fault with her.

- O, it was dreadful! Tom was so hard and unconcerned; if he had been crying on the floor, Maggie would have cried too. And there was the dinner, so nice; and she was so hungry. It was very bitter.

- Mr Tulliver felt very much as if the air had been cleared of obtrusive flies now the women were out of the room.

- Tom could build perfect pyramids of houses; but Maggie’s would never bear the laying on of the roof: it was always so with the things that Maggie made; and Tom had deduced the conclusion that no girls could ever make anything.

- Maggie lingered at a distance, looking like a small Medusa with her snakes cropped.

- The astronomer who hated women generally caused her so much puzzling speculation that she one day asked Mr. Stelling if all astronomers hated women, or whether it was only this particular astronomer. But forestalling his answer, she said —“I suppose it’s all astronomers; because, you know, they live up in high towers, and if the women came there they might talk and hinder them from looking at the stars.”

- If boys and men are to be welded together in the glow of transient feeling, they must be made of metal that will mix, else they inevitably fall asunder when the heat dies out.

- Tom bit his lips hard; he felt as if the tears were rising, and he would rather die than let them.

- Of those two young hearts Tom’s suffered the most unmixed pain, for Maggie, with all her keen susceptibility, yet felt as if the sorrow made larger room for her love to flow in, and gave breathing-space to her passionate nature. No true boy feels that; he would rather go and slay the Nemean lion, or perform any round of heroic labors, than endure perpetual appeals to his pity, for evils over which he can make no conquest.

- Saints and martyrs had never interested Maggie so much as sages and poets.

- But it isn’t for that, that I’m jealous for the dark women — not because I’m dark myself; it’s because I always care the most about the unhappy people. If the blond girl were forsaken, I should like her best. I always take the side of the rejected lover in the stories.” / “Then you would never have the heart to reject one yourself, should you, Maggie?” said Philip, flushing a little.

- “Pray, how have you shown your love, that you talk of, either to me or my father? By disobeying and deceiving us. I have a different way of showing my affection.” / “Because you are a man, Tom, and have power, and can do something in the world.” / “Then, if you can do nothing, submit to those that can.”

- “I shall be very difficult to please,” said Maggie, smiling, and holding up one of Lucy’s long curls, that the sunlight might shine through it. “A gentleman who thinks he is good enough for Lucy must expect to be sharply criticised.”

- I don’t know what may be in years to come. But I begin to think there can never come much happiness to me from loving; I have always had so much pain mingled with it. I wish I could make myself a world outside it, as men do.”

- “Shall I, wasting in despair, / Die because a woman’s fair?”

Quotes about Love

- “Tom’s not fond of reading. I love Tom so dearly, Luke — better than anybody else in the world. When he grows up, I shall keep his house, and we shall always live together. I can tell him everything he doesn’t know.”

- “I do love you, Tom.”

- “And I don’t love you, Maggie.”

- “I’d forgive you, if you forgot anything — I wouldn’t mind what you did — I’d forgive you and love you.” / “Yes, you’re a silly — but I never do forget things — I don’t.”

- What use was anything, if Tom didn’t love her?

- The need of being loved, the strongest need in poor Maggie’s nature.

- It is a wonderful subduer, this need of love — this hunger of the heart — as peremptory as that other hunger by which Nature forces us to submit to the yoke, and change the face of the world.

- “I’ll always be a good brother to you.”

- Maggie, moreover, had rather a tenderness for deformed things; she preferred the wry-necked lambs, because it seemed to her that the lambs which were quite strong and well made wouldn’t mind so much about being petted; and she was especially fond of petting objects that would think it very delightful to be petted by her. She loved Tom very dearly, but she often wished that he cared more about her loving him.

- He thought this sister of Tulliver’s seemed a nice little thing, quite unlike her brother; he wished he had a little sister. What was it, he wondered, that made Maggie’s dark eyes remind him of the stories about princesses being turned into animals? …. I think it was that her eyes were full of unsatisfied intelligence, and unsatisfied beseeching affection.

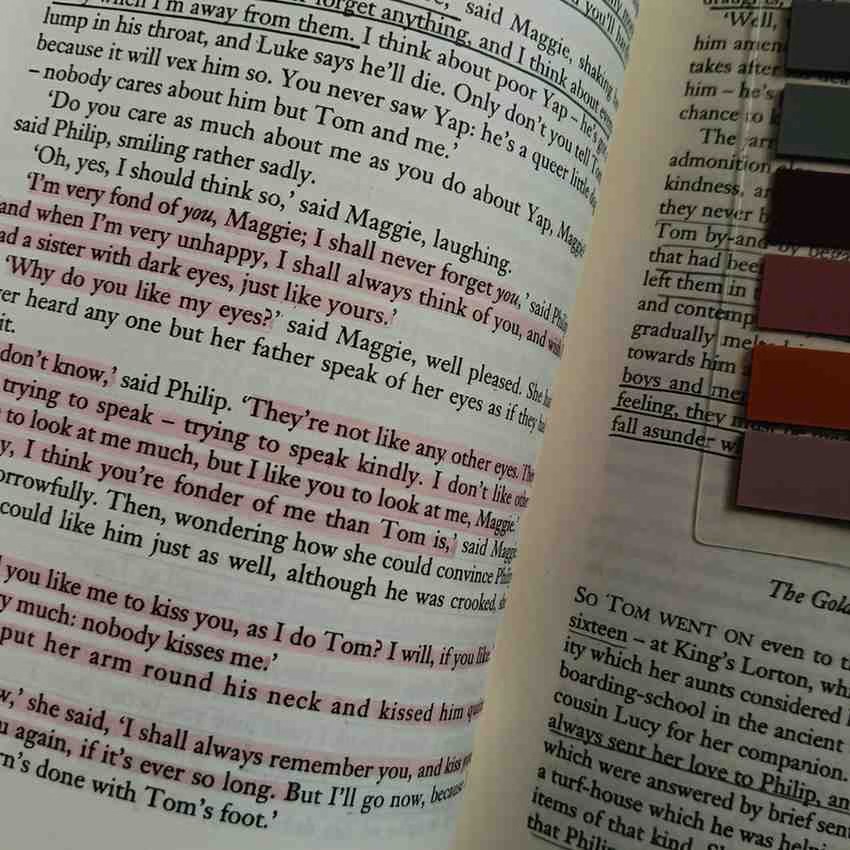

- “I’m very fond of you, Maggie; I shall never forget you,” said Philip, “and when I’m very unhappy, I shall always think of you, and wish I had a sister with dark eyes, just like yours.”

- “They’re not like any other eyes. They seem trying to speak — trying to speak kindly. I don’t like other people to look at me much, but I like you to look at me, Maggie.”

- And if life had no love in it, what else was there for Maggie?

- “You are very much more beautiful than I thought you would be.”

- “May I come again, then, to-morrow, or the next day, or next week?”

- “I’m very grateful to you for thinking of me all those years. It is very sweet to have people love us. What a wonderful, beautiful thing it seems that God should have made your heart so that you could care about a queer little girl whom you only knew for a few weeks!”

- “Ah, Maggie,” said Philip, almost fretfully, “you would never love me so well as you love your brother.” / “Perhaps not,” said Maggie, simply; “but then, you know, the first thing I ever remember in my life is standing with Tom by the side of the Floss, while he held my hand; everything before that is dark to me. But I shall never forget you, though we must keep apart.” / “Don’t say so, Maggie,” said Philip. “If I kept that little girl in my mind for five years, didn’t I earn some part in her? She ought not to take herself quite away from me.”

- If any woman could love him, surely Maggie was that woman; there was such wealth of love in her, and there was no one to claim it all. Then, the pity of it, that a mind like hers should be withering in its very youth, like a young forest-tree, for want of the light and space it was formed to flourish in! Could he not hinder that, by persuading her out of her system of privation? He would be her guardian angel; he would do anything, bear anything, for her sake — except not seeing her.

- “Well, Maggie, if we must part, let us try and forget it for one half hour; let us talk together a little while, for the last time.”

- “Let us only care about being together. We shall be friends in spite of separation. We shall always think of each other. I shall be glad to live as long as you are alive, because I shall think there may always come a time when I can — when you will let me help you in some way.”

- “I had never thought of your being my lover. It seemed so far off — like a dream — only like one of the stories one imagines — that I should ever have a lover.”

- “Don’t think of the past now, Maggie; think only of our love. If you can really cling to me with all your heart, every obstacle will be overcome in time; we need only wait. I can live on hope. Look at me, Maggie; tell me again it is possible for you to love me.”

- “No, Maggie, I will ask nothing; I will bear everything; I’ll wait another year only for a kiss, if you will only give me the first place in your heart.” / “No,” said Maggie, smiling, “I won’t make you wait so long as that.”

- If there were sacrifice in this love, it was all the richer and more satisfying.

- If you were in fault ever, if you had done anything very wrong, I should be sorry for the pain it brought you; I should not want punishment to be heaped on you. But you have always enjoyed punishing me; you have always been hard and cruel to me; even when I was a little girl, and always loved you better than any one else in the world, you would let me go crying to bed without forgiving me.

- “Tom, forgive me — let us always love each other;” and they clung and wept together.

- She and Stephen were in that stage of courtship which makes the most exquisite moment of youth, the freshest blossom-time of passion — when each is sure of the other’s love, but no formal declaration has been made, and all is mutual divination, exalting the most trivial word, the lightest gesture, into thrills delicate and delicious as wafted jasmine scent. The explicitness of an engagement wears off this finest edge of susceptibility; it is jasmine gathered and presented in a large bouquet.

- He is the fallen Adam with a soured temper. We are Adam and Eve unfallen, in Paradise.

- Surely the only courtship unshaken by doubts and fears must be that in which the lovers can sing together.

- In the provinces, too, where music was so scarce in that remote time, how could the musical people avoid falling in love with each other? Even political principle must have been in danger of relaxation under such circumstances; and the violin, faithful to rotten boroughs, must have been tempted to fraternize in a demoralizing way with a reforming violoncello.

- When Maggie was not angry, she was as dependent on kind or cold words as a daisy on the sunshine or the cloud; the need of being loved would always subdue her.

- “I should like to know what is the proper function of women, if it is not to make reasons for husbands to stay at home, and still stronger reasons for bachelors to go out.”

- But there came the necessity of walking home in the cool starlight, and with it the necessity of cursing his own folly, and bitterly determining that he would never trust himself alone with Maggie again. It was all madness.

- And if people happen to be lovers, what can be so delightful, in England, as a rainy morning? English sunshine is dubious; bonnets are never quite secure; and if you sit down on the grass, it may lead to catarrhs. But the rain is to be depended on. You gallop through it in a mackintosh, and presently find yourself in the seat you like best — a little above or a little below the one on which your goddess sits (it is the same thing to the metaphysical mind, and that is the reason why women are at once worshipped and looked down upon), with a satisfactory confidence that there will be no lady-callers.

- She was looking at the tier of geraniums as she spoke, and Stephen made no answer; but he was looking at her; and does not a supreme poet blend light and sound into one, calling darkness mute, and light eloquent? Something strangely powerful there was in the light of Stephen’s long gaze, for it made Maggie’s face turn toward it and look upward at it, slowly, like a flower at the ascending brightness.

- Stephen was mute; he was incapable of putting a sentence together, and Maggie bent her arm a little upward toward the large half-opened rose that had attracted her. Who has not felt the beauty of a woman’s arm? The unspeakable suggestions of tenderness that lie in the dimpled elbow, and all the varied gently lessening curves, down to the delicate wrist, with its tiniest, almost imperceptible nicks in the firm softness. A woman’s arm touched the soul of a great sculptor two thousand years ago, so that he wrought an image of it for the Parthenon which moves us still as it clasps lovingly the timeworn marble of a headless trunk. Maggie’s was such an arm as that, and it had the warm tints of life.

- “As if it were not enough that I’m entangled in this way; that I’m mad with love for you; that I resist the strongest passion a man can feel, because I try to be true to other claims; but you must treat me as if I were a coarse brute, who would willingly offend you. And when, if I had my own choice, I should ask you to take my hand and my fortune and my whole life, and do what you liked with them!

- “Maggie, if you loved me as I love you, we should throw everything else to the winds for the sake of belonging to each other. We should break all these mistaken ties that were made in blindness, and determine to marry each other.”

- “Oh, it is difficult — life is very difficult! It seems right to me sometimes that we should follow our strongest feeling; but then, such feelings continually come across the ties that all our former life has made for us — the ties that have made others dependent on us — and would cut them in two. If life were quite easy and simple, as it might have been in Paradise, and we could always see that one being first toward whom — I mean, if life did not make duties for us before love comes, love would be a sign that two people ought to belong to each other. But I see — I feel it is not so now; there are things we must renounce in life; some of us must resign love. Many things are difficult and dark to me; but I see one thing quite clearly — that I must not, cannot, seek my own happiness by sacrificing others. Love is natural; but surely pity and faithfulness and memory are natural too. And they would live in me still, and punish me if I did not obey them. I should be haunted by the suffering I had caused. Our love would be poisoned. Don’t urge me; help me — help me, because I love you.”

- He murmured forth in fragmentary sentences his happiness, his adoration, his tenderness, his belief that their life together must be heaven, that her presence with him would give rapture to every common day; that to satisfy her lightest wish was dearer to him than all other bliss; that everything was easy for her sake, except to part with her; and now they never would part; he would belong to her forever, and all that was his was hers — had no value for him except as it was hers.

- “Dearest! If you love me, you are mine. Who can have so great a claim on you as I have? My life is bound up in your love. There is nothing in the past that can annul our right to each other; it is the first time we have either of us loved with our whole heart and soul.”

- “Maggie — I believe in you; I know you never meant to deceive me; I know you tried to keep faith to me and to all.”

- Perhaps I feel about you as the artist does about the scene over which his soul has brooded with love; he would tremble to see it confided to other hands; he would never believe that it could bear for another all the meaning and the beauty it bears for him.

Quotes about (Bittersweet) Life

- “That old woman in the water’s a witch — they’ve out her in to find out whether she’s a witch or no, and if she swims she’s a witch, and if she’s drowned — and killed, you know— she’s innocent, and not a witch, but only a poor silly old woman. But what good would it do her then, you know, when she’s was drowned? Only, I suppose, she’d go to heaven, and God would make it up to her.”

- As at last the sobs were getting quieter, and the grinding less fierce, a sudden beam of sunshine, falling through the wire lattice across the worm-eaten shelves, made her throw away the Fetish and run to the window. The sun was really breaking out; the sound of the mill seemed cheerful again; the granary doors were open; and there was Yap, the queer white-and-brown terrier, with one ear turned back, trotting about and sniffing vaguely, as if he were in search of a companion.

- The willows and the reeds and the water had their happy whispering also. Maggie thought it would make a very nice heaven to sit by the pool in that way, and never be scolded.

- It was one of their happy mornings. They trotted along and sat down together, with no thought that life would ever change much for them: they would only get bigger and not go to school, and it would always be like the holidays; they would always live together and be fond of each other.

- These things would always be just the same to them. Tom thought people were at a disadvantage who lived on any other spot of the globe.

- There was hope in the air.

- Maggie could think for now comfort but to sit down by the holly, or wander by the hedgerow, and fancy it was all different, refashioning her little world into just what she should like it to be. Maggie’s was a troublesome life, and this was the form in which she took her opium.

- It was very pretty make-believe.

- No! she would run away and go to the gypsies, and Tom should never see her any more. That was by no means a new idea to Maggie; she had been so often told she was like a gypsy, and “half wild,” that when she was miserable it seemed to her the only way of escaping opprobrium, and being entirely in harmony with circumstances, would be to live in a little brown tent on the commons; the gypsies, she considered, would gladly receive her and pay her much respect on account of her superior knowledge.

- He looked with grave pity at the brother and sister for whom youth and sorrow had begun together.

- “Do remember to eat something on the way, dear.” Maggie’s heart went out toward this woman whom she had never liked, and she kissed her silently. It was the first sign within the poor child of that new sense which is the gift of sorrow — that susceptibility to the bare offices of humanity which raises them into a bond of loving fellowship, as to haggard men among the ice-bergs the mere presence of an ordinary comrade stirs the deep fountains of affection.

- The pride and obstinacy of millers and other insignificant people, whom you pass unnoticingly on the road every day, have their tragedy too; but it is of that unwept, hidden sort that goes on from generation to generation, and leaves no record — such tragedy, perhaps, as lies in the conflicts of young souls, hungry for joy, under a lot made suddenly hard to them, under the dreariness of a home where the morning brings no promise with it, and where the unexpectant discontent of worn and disappointed parents weighs on the children like a damp, thick air, in which all the functions of life are depressed; or such tragedy as lies in the slow or sudden death that follows on a bruised passion, though it may be a death that finds only a parish funeral. There are certain animals to which tenacity of position is a law of life — they can never flourish again, after a single wrench: and there are certain human beings to whom predominance is a law of life — they can only sustain humiliation so long as they can refuse to believe in it, and, in their own conception, predominate still.

- There is no hopelessness so sad as that of early youth, when the soul is made up of wants, and has no long memories, no superadded life in the life of others; though we who looked on think lightly of such premature despair, as if our vision of the future lightened the blind sufferer’s present.

- This sad chamber which was the centre of her world, was a creature full of eager, passionate longings for all that was beautiful and glad; thirsty for all knowledge; with an ear straining after dreamy music that died away and would not come near to her; with a blind, unconscious yearning for something that would link together the wonderful impressions of this mysterious life, and give her soul a sense of home in it.

- Sometimes Maggie thought she could have been contented with absorbing fancies; if she could have had all Scott’s novels and all Byron’s poems! — then, perhaps, she might have found happiness enough to dull her sensibility to her actual daily life. And yet they were hardly what she wanted. She could make dream-worlds of her own, but no dream-world would satisfy her now. She wanted some explanation of this hard, real life —

- Her brain would be busy with wild romances of a flight from home in search of something less sordid and dreary; she would go to some great man — Walter Scott, perhaps — and tell him how wretched and how clever she was, and he would surely do something for her.

- “But I can’t give up wishing,” said Philip, impatiently. “It seems to me we can never give up longing and wishing while we are thoroughly alive. There are certain things we feel to be beautiful and good, and we must hunger after them. How can we ever be satisfied without them until our feelings are deadened? I delight in fine pictures; I long to be able to paint such. I strive and strive, and can’t produce what I want. That is pain to me, and always will be pain, until my faculties lose their keenness, like aged eyes. Then there are many other things I long for,”— here Philip hesitated a little, and then said — “things that other men have, and that will always be denied me. My life will have nothing great or beautiful in it; I would rather not have lived.”

- “The greatest of painters only once painted a mysteriously divine child; he couldn’t have told how he did it, and we can’t tell why we feel it to be divine. I think there are stores laid up in our human nature that our understandings can make no complete inventory of.”

- “It would make me in love with this world again, as I used to be; it would make me long to see and know many things; it would make me long for a full life.”

- “Poetry and art and knowledge are sacred and pure.” / “But not for me, not for me,” said Maggie, walking more hurriedly; “because I should want too much. I must wait; this life will not last long.”

- “I’m cursed with susceptibility in every direction, and effective faculty in none. I care for painting and music; I care for classic literature, and mediaeval literature, and modern literature; I flutter all ways, and fly in none.” / “But surely that is a happiness to have so many tastes — to enjoy so many beautiful things, when they are within your reach,” said Maggie, musingly. “It always seemed to me a sort of clever stupidity only to have one sort of talent — almost like a carrier-pigeon.”

- “I used to think I could never bear life if it kept on being the same every day, and I must always be doing things of no consequence, and never know anything greater. But, dear Philip, I think we are only like children that some one who is wiser is taking care of. Is it not right to resign ourselves entirely, whatever may be denied us? I have found great peace in that for the last two or three years, even joy in subduing my own will.”

- “It is better for me to do without earthly happiness altogether. I never felt that I had enough music —”

- She felt the half-remote presence of a world of love and beauty and delight, made up of vague, mingled images from all the poetry and romance she had ever read, or had ever woven in her dreamy reveries.

- “I think I should have no other mortal wants, if I could always have plenty of music. It seems to infuse strength into my limbs, and ideas into my brain. Life seems to go on without effort, when I am filled with music. At other times one is conscious of carrying a weight.”

- Life was certainly very pleasant just now; it was becoming very pleasant to dress in the evening, and to feel that she was one of the beautiful things of this spring-time.

- Maggie’s destiny, then, is at present hidden, and we must wait for it to reveal itself like the course of an unmapped river; we only know that the river is full and rapid, and that for all rivers there is the same final home.

- But this must end some time, perhaps it ended very soon, and only seemed long, as a minute’s dream does.

- “I think I am quite wicked with roses; I like to gather them and smell them till they have no scent left.”

- “I have nothing but the past to live upon.”

- “I’m very wretched! I wish I could have died when I was fifteen. It seemed so easy to give things up then; it is so hard now.” The poor child threw her arms round her aunt’s neck, and fell into long, deep sobs.

- Did she lie down in the gloomy bedroom of the old inn that night with her will bent unwaveringly on the path of penitent sacrifice? The great struggles of life are not so easy as that; the great problems of life are not so clear.

- “I have no heart to begin a strange life again. I should have no stay. I should feel like a lonely wanderer, cut off from the past.

Quotes about Nature

- I am in love with moistness, and envy the white ducks that are dipping their heads far into the water here among the withes, unmindful of the awkward appearance they make in the drier world above.

- The mill was a little world apart from her outside everyday life.

- Nature has the deep cunning which hides itself under the appearance of openness, so that simple people think they can see through her quite well, and all the while she is secretly preparing a refutation of their confident prophecies.

- The wood I walk in on this mild May day, with the young yellow-brown foliage of the oaks between me and the blue sky, the white star-flowers and the blue-eyed speedwell and the ground ivy at my feet, what grove of tropic palms, what strange ferns or splendid broad-petalled blossoms, could ever thrill such deep and delicate fibres within me as this home scene? These familiar flowers, these well-remembered bird-notes, this sky, with its fitful brightness, these furrowed and grassy fields, each with a sort of personality given to it by the capricious hedgerows — such things as these are the mother-tongue of our imagination, the language that is laden with all the subtle, inextricable associations the fleeting hours of our childhood left behind them. Our delight in the sunshine on the deep-bladed grass to-day might be no more than the faint perception of wearied souls, if it were not for the sunshine and the grass in the far-off years which still live in us, and transform our perception into love.

- How glad Tom was to see the last yellow leaves fluttering before the cold wind! The dark afternoons and the first December snow seemed to him far livelier than the August sunshine.

- There was no gleam, no shadow, for the heavens, too, were one still, pale cloud; no sound or motion in anything but the dark river that flowed and moaned like an unresting sorrow. But old Christmas smiled as he laid this cruel-seeming spell on the outdoor world, for he meant to light up home with new brightness, to deepen all the richness of indoor color, and give a keener edge of delight to the warm fragrance of food.

- It was a dark, chill, misty morning, likely to end in rain — one of those mornings when even happy people take refuge in their hopes.

- These Rhine castles thrill me with a sense of poetry; they belong to the grand historic life of humanity, and raise up for me the vision of an echo. But these dead-tinted, hollow-eyed, angular skeletons of villages on the Rhone oppress me with the feeling that human life — very much of it — is a narrow, ugly, grovelling existence, which even calamity does not elevate.

- “How strange and unreal the trees and flowers look with the lights among them!” said Maggie, in a low voice. “They look as if they belonged to an enchanted land, and would never fade away; I could fancy they were all made of jewels.”

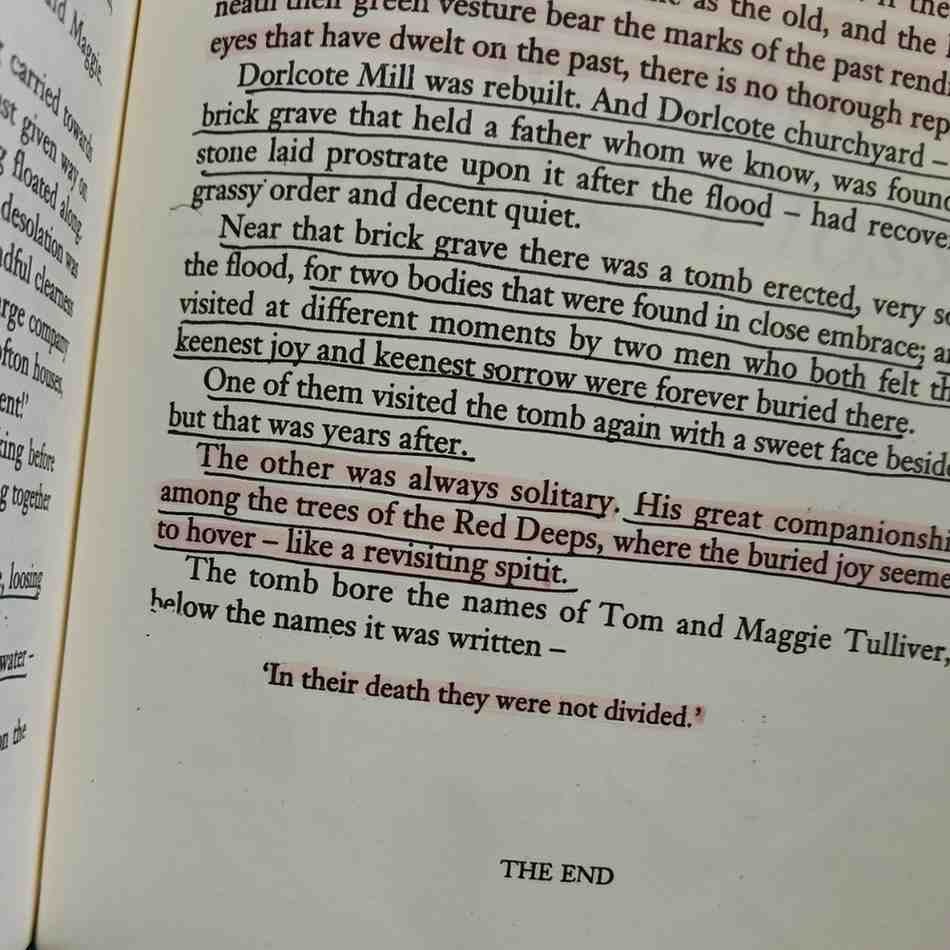

- Nature repairs her ravages — repairs them with her sunshine, and with human labor. The desolation wrought by that flood had left little visible trace on the face of the earth, five years after. The fifth autumn was rich in golden cornstacks, rising in thick clusters among the distant hedgerows; the wharves and warehouses on the Floss were busy again, with echoes of eager voices, with hopeful lading and unlading. And every man and woman mentioned in this history was still living, except those whose end we know. Nature repairs her ravages, but not all. The uptorn trees are not rooted again; the parted hills are left scarred; if there is a new growth, the trees are not the same as the old, and the hills underneath their green vesture bear the marks of the past rending. To the eyes that have dwelt on the past, there is no thorough repair.

Quotes about Education

- “There’s no greater advantage you can give him than a good education.”

- “I want him to know figures, and write like print, and see into things quick, and know what folks mean, and how ro wrap things up in words as aren’t actionable.”

- When land is gone and money’s spent / Then learning is most excellent.

- For the first time in his life he had a painful sense that he was all wrong somehow.

- But there are two expensive forms of education, either of which a parent may procure for his son by sending him as solitary pupil to a clergyman: one is the enjoyment of the reverend gentleman’s undivided neglect; the other is the endurance of the reverend gentleman’s undivided attention.

- It is astonishing what a different result one gets by changing the metaphor!

- “Girls can’t do Euclid; can they, sir?” / “They can pick up a little of everything, I dare say,” said Mr. Stelling. “They’ve a great deal of superficial cleverness; but they couldn’t go far into anything. They’re quick and shallow.” Tom, delighted with this verdict, telegraphed his triumph by wagging his head at Maggie, behind Mr. Stelling’s chair. As for Maggie, she had hardly ever been so mortified. She had been so proud to be called “quick” all her little life, and now it appeared that this quickness was the brand of inferiority. It would have been better to be slow, like Tom.

- “I’m very fond of Greek history, and everything about the Greeks. I should like to have been a Greek and fought the Persians, and then have come home and have written tragedies, or else have been listened to by everybody for my wisdom, like Socrates, and have died a grand death.” (Philip, you perceive, was not without a wish to impress the well-made barbarian with a sense of his mental superiority.)

- How should Mr. Stelling be expected to know that education was a delicate and difficult business, any more than an animal endowed with a power of boring a hole through a rock should be expected to have wide views of excavation?

- Tom had felt some disgust on learning that Hector and Achilles might possibly never have existed.

Quotes about Worldliness

- A perfectly sane intellect is hardly at home in this insane world.

- “This is a puzzlin’ world.”

- It is always chilling in friendly intercourse, to say you have no opinion to give. And if you deliver an opinion at all, it is mere stupidity not to do it with an air of conviction, and well-founded knowledge.

- A man with the milk of human kindness in him can scarcely abstain form doing a good-natured action, and one cannot be good-natured all round. Nature herself occasionally quarters an inconvenient parasite on an animal towards whom she has otherwise no ill-will. What then? We admire her care for the parasite.

- She should like him to out the worms on the hook for her, although she accepted his word when he assured her that worms couldn’t feel (it was Tom’s private opinion that it didn’t much matter if they did).

- While no individual Dodson was satisfied with any other individual Dodson, each was satisfied, not only with him or her self, but with the Dodsons collectively.

- It is a pathetic sight, and a striking example of the complexity introduced into the emotions by a high state of civilization — the sight of a fashionably-dressed female in grief.

- Uncle Pullet belonged to that extinct class of British yeoman who, dressed in good broadcloth, paid high rates and taxes, went to church, and ate a particularly good dinner on Sunday, without dreaming that the British constitution in Church and State had a traceable origin any more than the solar system and the fixed stars.

- Poor relations are undeniably irritating — their existence is so entirely uncalled for on our part, and they are almost always very faulty people.

- The linen’s so in order, as if I was to die to-morrow I shouldn’t be ashamed.

- Anger and jealousy can no more bear to lose sight of their objects than love.

- When people were grown up, he considered, nobody inquired about their writing and spelling; when he was a man, he should be master of everything, and do just as he liked.

- It was evident to him that life, complicated not only with the Latin grammar but with a new standard of English pronunciation, was a very difficult business, made all the more obscure by a thick mist of bashfulness.

- It was doubtless an ingenious idea to call the camel the ship of the desert, but it would hardly lead one far in training that useful beast. O Aristotle! if you had had the advantage of being “the freshest modern” instead of the greatest ancient, would you not have mingled your praise of metaphorical speech, as a sign of high intelligence, with a lamentation that intelligence so rarely shows itself in speech without metaphor — that we can so seldom declare what a thing is, except by saying it is something else?

- If you think a lad of thirteen would have been so childish, you must be an exceptionally wise man, who, although you are devoted to a civil calling, requiring you to look bland rather than formidable, yet never, since you had a beard, threw yourself into a martial attitude, and frowned before the looking-glass. It is doubtful whether our soldiers would be maintained if there were not pacific people at home who like to fancy themselves soldiers. War, like other dramatic spectacles, might possibly cease for want of a “public.”

- “We’ll do as we’d be done by; for if my children have got no other luck, they’ve got an honest father and mother.”

- “When you come to money business, and you may be taking one man’s dinner away to make another man’s breakfast.”

- It was intolerable to think of being poor and looked down upon all one’s life. He would provide for his mother and sister, and make every one say that he was a man of high character. He leaped over the years in this way, and, in the haste of strong purpose and strong desire, did not see how they would be made up of slow days, hours, and minutes.

- “But you youngsters nowadays think you’re to begin with living well and working easy; you’ve no notion of running afoot before you get horseback.”

- “The world isn’t made of pen, ink, and paper, and if you’re to get on in the world, young man, you must know what the world’s made of.”

- To suppose that Wakem had the same sort of inveterate hatred toward Tulliver that Tulliver had toward him would be like supposing that a pike and a roach can look at each other from a similar point of view. The roach necessarily abhors the mode in which the pike gets his living, and the pike is likely to think nothing further even of the most indignant roach than that he is excellent good eating; it could only be when the roach choked him that the pike could entertain a strong personal animosity.

- Mankind is not disposed to look narrowly into the conduct of great victors when their victory is on the right side.

- “Give me a kiss, Bessy, and let us bear one another no ill-will; we shall never be young again — this world’s been too many for me.”

- If, in the maiden days of the Dodson sisters, their Bibles opened more easily at some parts than others, it was because of dried tulip-petals, which had been distributed quite impartially, without preference for the historical, devotional, or doctrinal.

- To be honest and poor was never a Dodson motto, still less to seem rich though being poor; rather, the family badge was to be honest and rich, and not only rich, but richer than was supposed.

- She remained bewildered in this empty life. Why that should have happened to her which had not happened to other women, remained an insoluble question.

- All the miseries of her young life had come from fixing her heart on her own pleasure, as if that were the central necessity of the universe.

- Kept aloof from all practical life as Philip had been, and by nature half feminine in sensitiveness, he had some of the woman’s intolerant repulsion toward worldliness and the deliberate pursuit of sensual enjoyment; and this one strong natural tie in his life — his relation as a son — was like an aching limb to him. Perhaps there is inevitably something morbid in a human being who is in any way unfavorably excepted from ordinary conditions, until the good force has had time to triumph; and it has rarely had time for that at two-and-twenty. That force was present in Philip in much strength, but the sun himself looks feeble through the morning mists.

- Perhaps the luck was beginning to turn; perhaps the Devil didn’t always hold the best cards in this world.

Quotes about Sorrow and Death

- These bitter sorrows of childhood! when sorrow is all new and strange, when hope has not yet got wings to fly beyond the days and weeks, and the space from summer to summer seems measureless.

- We learn to restrain ourselves as we get older. We keep apart when we have quarreled, express ourselves in well-bred phrases, and in this way preserve a dignified alienation, showing much firmness on one side, and swallowing much grief on the other.

- So ended the sorrows of this day.

- There were passions at war in Maggie at that moment to have made a tragedy, if tragedies were made by passion only; but the essential αμ έγεθοδ which was present in the passion was wanting to the action; the utmost Maggie could do, with a fierce thrust of her small brown arm, was to push poor little pink-and-white Lucy into the cow-trodden mud.Then Tom could not restrain himself, and gave Maggie two smart slaps on the arm as he ran to pick up Lucy, who lay crying helplessly. Maggie retreated to the roots of a tree a few yards off, and looked on impenitently. Usually her repentance came quickly after one rash deed, but now Tom and Lucy had made her so miserable, she was glad to spoil their happiness,–glad to make everybody uncomfortable. Why should she be sorry? Tom was very slow to forgive her, however sorry she might have been.

- Death was not to be a leap; it was to be a long descent under thickening shadows.

- She thought it was part of the hardship of her life that there was laid upon her the burthen of larger wants than others seemed to feel — that she had to endure this wide, hopeless yearning for that something, whatever it was, that was greatest and best on this earth.

- She was as lonely in her trouble as if she had been the only girl in the civilized world of that day who had come out of her school-life with a soul untrained for inevitable struggles.

- “Our life is determined for us; and it makes the mind very free when we give up wishing, and only think of bearing what is laid upon us, and doing what is given us to do.”

- “The Muses were uncomfortable goddesses, I think —”

- “I’m determined to read no more books where the blond-haired women carry away all the happiness. I should begin to have a prejudice against them. If you could give me some story, now, where the dark woman triumphs, it would restore the balance.”

- She used to think in that time that she had made great conquests, and won a lasting stand on serene heights above worldly temptations and conflict. And here she was down again in the thick of a hot strife with her own and others’ passions. Life was not so short, then, and perfect rest was not so near as she had dreamed when she was two years younger. There was more struggle for her, and perhaps more falling.

- “One gets a bad habit of being unhappy.”

- “I often hate myself, because I get angry sometimes at the sight of happy people.”

- The happiest women, like the happiest nations, have no history.

- “I will bear it, and bear it till death. But how long it will be before death comes! I am so young, so healthy. How shall I have patience and strength? Am I to struggle and fall and repent again? Has life other trials as hard for me still?”

- The boat reappeared, but brother and sister had gone down in an embrace never to be parted; living through again in one supreme moment the days when they had clasped their little hands in love, and roamed the daisied fields together.

- “In their death they were not divided.”

Phew, that was long.

So, these were the beautiful, amazing George Eliot quotes from The Mill on the Floss, and they’re clearly a very obvious example of her clever and poetic writing style.

Look out for the next post: Classy Literature Quotes from Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations.

Also, if you haven’t already, sign up for our newsletter down below. We talk about literature and philosophy and everything in between.